Out & About: Watching De Beers Grow Diamonds in Oregon

Editor-in-Chief Michelle Graff shares her opinions on the state of the lab-grown diamond market following a trip to the Lightbox factory.

Some 14 years later, I received another invitation to take a trip with De Beers, this time to observe a different kind of operation—the factory where it grows diamonds outside Portland, Oregon.

I find the science behind growing diamonds much more interesting than all the tedious back-and-forth about lab-grown vs. natural (and I’m forbidden from having that debate anyway, per National Jeweler’s Lenore Fedow).

I think both have, and will continue to have, their place in the industry; what exactly that place will be—the stone of choice for engagement rings, the main driver of fashion jewelry, or some mix thereof—remains to be seen, particularly in this unpredictable climate.

On a personal note, I prefer natural diamonds to lab-grown, particularly for big milestone gifts to myself, though I can see the appeal of lab-grown diamond jewelry for more “fun” pieces, particularly those set with a pink or blue diamond, which are largely unattainable due to their cost.

But those pinks and blues are only part of the production run at the Lightbox, which I visited in early November with a group of journalists on a tour led by the site’s general manager, Adam O’Grady.

Stepping Inside

Lightbox is in Gresham, Oregon, about 25 minutes east of Portland.

De Beers chose Portland because it needed to build the factory somewhere that has a reasonable cost-per-kilowatt for energy, has access to renewable sources of energy, and doesn’t get too hot in the summer.

Portland checks all three boxes, though it’s worth pointing out that the extreme weather patterns brought about by climate change are a concern to Lightbox just as they are a concern to the diamond miners that rely on ice roads. Portland, where it normally doesn’t get much hotter than 75-80° F, saw temps soar past 100° F this past summer.

The Lightbox factory employs about 80 people, 45 of whom are employed in direct production. It’s staffed 24/7 and its reactors run around-the-clock as well.

Mounted at the front entrance to the factory is a massive screen monitoring each reactor. Someone on the tour compared it to the control room on the Starship Enterprise, but as a Star Wars fan I didn’t get the reference.

The screen shows you which reactors in the factory are actively growing diamonds and which are down due to mechanical issues or scheduled maintenance.

For those that are active, the screen shows what they are growing—meaning size and color of diamond—and how much longer they have to cook, so to speak, before the diamonds are done.

How They Grow

The Lightbox factory uses chemical-vapor deposition (CVD) technology to grow diamonds.

CVD is a newer, and more expensive process than the high-pressure, high-temperature (HPHT) method mostly used to grow industrial-grade diamonds.

CVD involves growing substances atom-by-atom on a substrate material. In the case of Lightbox, that substrate material is diamond.

O’Grady told us that De Beers manufactures the substrate it uses for Lightbox diamonds on site, setting aside a small amount of production each day for future diamonds.

The diamond substrate plates are placed on a carrier by a robot, which is quicker and saves the factory’s employees from a tedious task, before they are delivered to their designated reactors.

To transform the plates, which to me look like gray Listerine strips, into actual stones, gases are pumped into each reactor and the machine is heated up to 6,000° C (10,832° F). The mix of gases depends on what the machine is growing: white, pink or blue diamonds.

O’Grady said it takes “a couple hundred hours to grow a couple of hundred stones” and, generally speaking, the bigger the stone needs to be, the longer it has to cook.

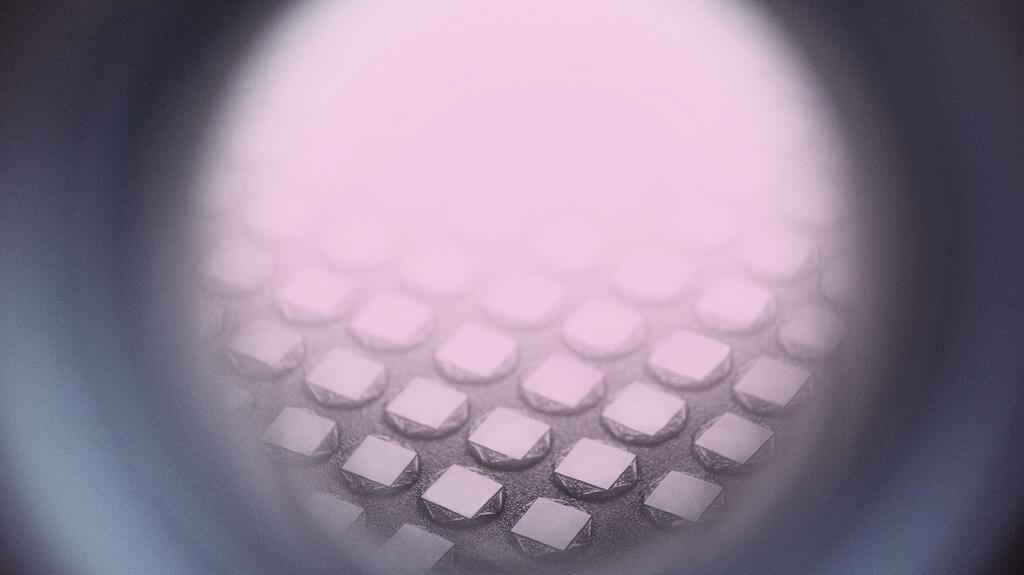

Each reactor is equipped with a peephole of sorts that you can look through to see the diamonds as they grow.

These are less necessary than they used to be since each machine is computer-monitored, O’Grady told me, but “people still like looking in them.” (It’s a bit like peeking in the oven to check on your cinnamon rolls; I understand the appeal.)

So, someone asked O’Grady, is the Lightbox factory the most high-tech diamond-growing facility in the world? “I think it’s safe to assume we are at the top end of that table,” he said.

After Growth

Once the diamonds are done, some initial cutting and polishing is done on-site, though the stones are not fully finished there. They are shipped to a cutting and polishing factory in India before being set into jewelry.

The pink and blue stones are HPHT treated post-growth to improve their color saturation and consistency, while all 2-carat and stones for “Finest,” its new premium line, are also HPHT treated to improve their color to D, E or F and their clarity to VVS. De Beers has just begun disclosing these treatments to consumers.

As you might remember, when De Beers launched Lightbox to much uproar at the Vegas shows in 2018, it introduced a strict pricing structure, $800/carat, and said it was marketing it as a “fun” product for somewhat-less-special special occasions, like a Sweet 16, positioning natural diamonds as the stone of choice for more substantial milestones.

In the years since, that uproar has calmed down as the lab-grown diamond market has evolved and the brand has evolved too, expanding beyond its originally declared mission, growing bigger, better diamonds.

The 2-carat diamonds I peeped growing in Portland are a new addition for Lightbox, as is the sale of loose diamonds, and “Finest,” the aformentioned premium line of D-to-F color, VVS diamonds it launched in August. “Finest” diamonds are priced at $1,500/carat.

I am curious to see where Lightbox, and the lab-grown market, will go from here.

In a forecast published this fall, diamond industry analyst Paul Zimnisky wrote that in the long term, growth in the sector will come mainly in fashion jewelry and industrial diamonds, a forecast I initially agreed with but then began to waver on following some recent headlines.

Signet Jewelers announced during its Q3 earnings call earlier this month that it is expanding its selection of lab-grown diamonds in some of its bestselling bridal lines.

The Knot’s latest survey showed that people’s stances on lab-grown stones—not just diamonds but moissanite as well—are softening when it comes to engagement rings.

And, as I noted above, De Beers is growing bigger, better diamonds and now also selling loose Lightbox stones, which seem destined for engagement rings.

While none of this is hard proof of where the market is definitively headed, what is certain is that years from now, people will find it hard to believe there was ever so much debate about lab-grown diamonds.

They’ll be like Prohibition (seems so strange now to think alcohol was once illegal, right?) or cannabis, which in my relatively short lifetime, has gone from being illegal everywhere to being legal in some form in all but 12 states.

People’s perspectives on what’s good or bad, what’s acceptable or unacceptable, are always changing. What’s hotly debated among members of one generation often isn’t even a point of conversation with the next.

The Latest

Said to be the first to write a jewelry sales manual for the industry, Zell is remembered for his zest for life.

The company outfitted the Polaris Dawn spaceflight crew with watches that will later be auctioned off to benefit St. Jude’s.

A buyer paid more than $100,000 for the gemstone known as “Little Willie,” setting a new auction record for a Scottish freshwater pearl.

Supplier Spotlight Sponsored by GIA.

Anita Gumuchian created the 18-karat yellow gold necklace using 189 carats of colored gemstones she spent the last 40 years collecting.

The giant gem came from Karowe, the same mine that yielded the 1,109-carat Lesedi La Rona and the 1,758-carat Sewelô diamond.

The three-stone ring was designed by Shahla Karimi Jewelry and represents Cuoco, her fiancé Tom Pelphrey, and their child.

Supplier Spotlight Sponsored by GIA

The Manhattan jewelry store has partnered with Xarissa B. of Jewel Boxing on a necklace capsule collection.

Acting as temporary virtual Post-it notes, Notes are designed to help strengthen mutual connections, not reach new audiences.

The jewelry historian discusses the history and cultural significance of jewelry throughout time and across the globe.

From fringe and tassels to pieces that give the illusion they are in motion, jewelry with movement is trending.

The designer and maker found community around her Philadelphia studio and creative inspiration on the sidewalks below it.

The change to accepted payment methods for Google Ads might seem like an irritation but actually is an opportunity, Emmanuel Raheb writes.

The industry consultant’s new book focuses on what she learned as an athlete recovering from a broken back.

The fair will take place on the West Coast for the first time, hosted by Altana Fine Jewelry in Oakland, California.

Hillelson is a second-generation diamantaire and CEO of Owl Financial Group.

Submissions in the categories of Jewelry Design, Media Excellence, and Retail Excellence will be accepted through this Friday, Aug. 23.

Known as “Little Willie,” it’s the largest freshwater pearl found in recent history in Scotland and is notable for its shape and color.

Clements Jewelers in Madisonville cited competition from larger retailers and online sellers as the driving factor.

The gemstone company is moving to the Ross Metal Exchange in New York City’s Diamond District.

Most of the 18th century royal jewelry taken from the Green Vault Museum in Dresden, Germany, in 2019 went back on display this week.

The Pittsburgh jeweler has opened a store in the nearby Nemacolin resort.

With a 40-carat cabochon emerald, this necklace is as powerful and elegant as a cat.

The Erlanger, Kentucky-based company was recognized for its reliability when it comes to repairs and fast turnaround times.

Unable to pay its debts, the ruby and sapphire miner is looking to restructure and become a “competitive and attractive” company.

The trend forecaster’s latest guide has intel on upcoming trends in the jewelry market.